Egyptian Blue Faience

The monthly ArtSmart Roundtable brings together some of the best art-focused travel blogs to post on a common theme. This month we are discussing Color! Color has enchanted artists and art lovers for centuries and we’ve picked some exciting topics; you can find links below for the rest of the group’s posts. I love bright colors, contrasting color, subtle transitions of color, and rich tones, but this month I want to talk about one particularly unique color which is intrinsically tied in my mind to entire collection of objects. I have always been fascinated by Ancient Egyptian blue Faience.

The iconic Blue Hippopotamus at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is one of the most well-known blue faience pieces. It was created in approximately 1981–1885 BCE in Middle Egypt.

While the technology to make faience was known to the Mesopotamians, Greeks and Romans, it was the ancient Egyptians that produced massive quantities of blue decorative items as grave goods which are now displayed in most museums. These Egyptian blue objects range from a deep cerulean to robins egg color to a green-blue hue. There is a depth and luminosity to this color that comes directly from how the objects were made.

18.5cm blue glazed composition ushabti of Psamtek, son of Sebarekhyt, ca. 600-300 BCE (Photo: British Museum)

But what is blue faience?

Faience is actually a glass. When heated to 4500 Fahrenheit, quartz sand, lime and sodium carbonate (aka “soda”) melt and fuse to form a glass. Smelting and kiln technology could support these temperatures. Modern archaeologists have reconstructed these furnaces to understand the process and have found the technology to be very sophisticated. Raw glass ingots were made in tremendous furnaces, chipped and then melted inside a form resulting in these objects. Color could be mixed in when forming the ingot or applied as a powder inside the mold to appear mostly on the object’s surface surface. The colored faience could also be melted around a composition, or ceramic, object.

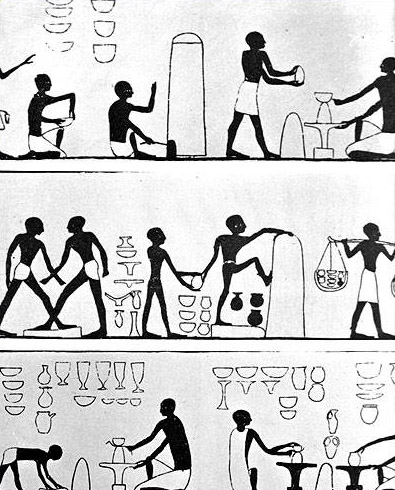

Ancient Egyptian wall-painting depicting pottery scenes from from Tomb #2, Beni Hasan, c. 1900 BCE. (Photo: Rockefeller Archaeological Museum)

The pigments to produce a blue color would have been readily available. Since bronze is predominantly copper mixed with smaller amounts of tin, lead, nickel, or iron, a common by-product of bronze manufacturing is colorful blue or green copper salts (like CuCO3). Given their potential presence in kiln or furnaces already, this may have unintentionally produced the first color faience.

Copper salts were used to give this ushapti it’s blue-green color. (Photo: Medusa Art Auction House)

Cobalt oxides (CoO, CO2O3) or cobalt tin salts were available in the environment and create a lovely cerulean blue color. (While unknown to the Egyptians, cobalt aluminum salts create a darker color which today is known as Prussian Blue.)

As far as the other ingredients in faience, sodium carbonate, also known as soda or natron, was gathered from dry lake beds in Egypt. It was an integral part of the mummification process because of hygroscopic, or water absorbing, properties.

Assortment of Egyptian Ushabti, including some beautiful blue faience ones from the Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Egyptian funerary practices created a huge market for faience objects. Small mummy-like figurines call ushapti were produced to represent servants that would serve the deceased in the afterlife. Amulets and miniature Gods and Goddesses were included in the mummy’s wrapping for protection. The quality of these objects seems to suggest a massive commercial operation with more expensive and fine-crafted pieces for the rich and simple ones for the poor.

I remain fascinated by these charming and gloriously blue objects. I only have a tiny art collection today, but some day I hope to have my very own Ancient Egyptian blue faience ushabti. (Service in the afterlife not required.)

If you’re interested in color and artistic materials, I would recommend Bright Earth: Art and the Invention of Color by Philip Ball. I’m a bit of an artist’s materials nerd myself and think this is a great introduction.

For the rest of the November ArtSmart Roundtable, see:

- Erin of A Sense of Place – What Went into Medieval Pigments and Where’d They Come From?

- Murissa of the Wanderful Traveler – A Personal Account: Six Degrees of Separation and J.M.W. Turner’s Use of Colour

- Lesley of the CultureTripper – Canadian color field painter William Perehudoff at Berry Campbell Gallery, New York

- Jenna of This Is My Happiness – coming soon…

- Ashley of No Onions, Extra Pickles – coming soon…

And don’t forget to “like” our group on Facebook for art & travel news!

Oh my goodness, what a fascinating post, Christina. Loved all the details on technique and would LOVE to come across a box of assorted blue faience Ushabti like the one shown. Gorgeous, gorgeous, gorgeous!

LikeLike

Thanks Lesley! Yes, these blue Ushabti are so gorgeous! If only there were just boxes of them just laying around for collectors. 🙂

LikeLike

Gorgeous! I love the colour it produces. I hope you get your own one day and now so do I. What a treasure and a fascinating post.

LikeLike

Love! Emory has a collection of faience pieces in their Ancient Egyptian section, and I always loved how the blue pops around all the warmer toned objects. I always knew it was a glassmaking process, but we never really went into the chemical process. Now I know.

LikeLike

Thanks Erin. I’ve always been enchanted by the blue color too. 🙂 It’s amazing to think that it was actually hard to NOT make the faience blue because of all the copper salts in the furnaces left over from bronze making.

LikeLike