The Life of A Painting: Leonardo da Vinci’s St. Jerome in the Wilderness

We take it for granted that paintings should be shown behind glass, watched by security, and protected in museums. However, for centuries a piece of art was just another personal possession. Someone could have a painting altered just as easily as having pants hemmed. Even pieces by the great masters were not immune to harsh treatment. Even an incredible painting by the Renaissance genius Leonardo da Vinci was carved up and nearly lost.

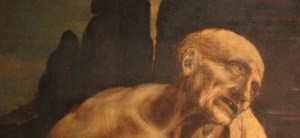

Leonardo da Vinci “Saint Jerome in the Wilderness (unrestored)”, Vatican Museums (Pinacoteca), Rome (Photo: Wikimedia)

Maybe because he primarily considered himself to be an engineer, Leonardo da Vinci did not produce a lot of finished paintings. He is known for reworking and revisiting his pieces over and over again; for example, he continued to work on the “Mona Lisa” another 11 years after he (supposedly) finished it. He also experimented with materials and techniques. His approach to painting with oil glazes changed over time and he famously used an new fresco method for the “Last Supper” which caused condition problems almost immediately. Leonardo da Vinci’s “St. Jerome in the Wilderness” is a half-completed piece but is valuable because of its rarity and for what is teaches us about his technique and approach to visual art.

“St. Jerome in the Wilderness” dates to approximately 1480. It shows the emaciated hermit saint in a barren, rocky landscape. An extreme penitent, he holds a stone to be used for self-mortification. According to legend, St. Jerome tamed a wild lion by removing a thorn from its paw and so a lion watches in the foreground of the painting with a tense, almost menacing, open mouth. There is a pain and grotesqueness to this work that defies the Renaissance ideal of beauty and symmetry but makes the painting so mesmerizing.

Close up of Leonardo da Vinci, “Saint Jerome in the Wilderness” today. Restoration has removed some of the very obvious seams (especially on the shoulder) where the panels were put back together.

I have always been amazed by the anatomical detail in the neck of St. Jerome. The tendons and sparse muscles are rendered in exquisite, almost painful detail. Da Vinci’s study of human anatomy through clandestine dissections is very evident here and this image shows a mastery of human physiology. The composition of the painting is also very new and show’s da Vinci’s creativity. The straining and rigid saint forms a trapezoid shape which is balanced by the relaxed S-curve of the lion below.

Viewed from below, you can see where Leonardo da Vinci, “Saint Jerome in the Wilderness” was cut apart.

As an unfinished piece, “St. Jerome in the Wilderness” would have likely stayed in da Vinci’s possession but it is not clear what happened to it after his death in 1519 in France. The work only really surfaces in the 19th century when Napoleon’s uncle, Cardinal Joseph Fesch, discovered pieces of the painting in a Roman shoemaker’s shop. “St. Jerome in the Wilderness” had been cut into 5 pieces. Reportedly the head portion was used as a box top and the back of the bottom two-thirds was being used as part of a work bench. Cardinal Fesch managed to recover all the pieces and reassembled the painting. After his death, the piece was purchased by Pope Pius IX in 1856. It is now on display in the Vatican Museum Pinacoteca.

If you look closely at the unrestored image at the top of the page, you can see some traces of where the painting had been cut apart. The seams are even more obvious in person if you look at the painting at an angle so that the light grazes across the surfaces. I took the picture above while at the Vatican which clearly shows the square piece cut out around the Saint’s face.

It’s incredible that this painting wasn’t lost completely, that all the pieces were recovered, and that it could be restored. Even half finished, “St. Jerome in the Wilderness” is a beautiful image. It connects to da Vinci’s notebooks of anatomical drawings, illustrates his creative use of space, and provides an example of an emotional and “ugly” image. Among da Vinci’s catalog, this is a rare painting which almost didn’t survive.

I remember the painting but didn’t know all of this, Christina, so thanks for that. It’s an extraordinary work. One of the first books I bought when I began my art history studies was a bible and read it cover to cover. One cannot understand most Western art if you don’t know the biblical stories and stories/attributes of the saints. Also Bullfinch’s mythology.

LikeLike